EVENT

Japanese Internment

1942EVENT TYPE Canadian History

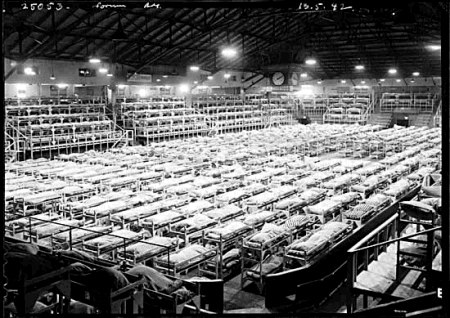

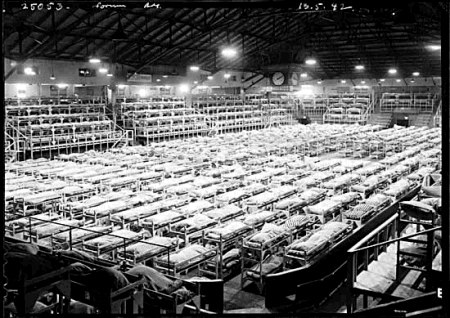

The bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, incited fear amongst British Columbians and aggravated deeply rooted racist attitudes towards Japanese immigrants. Already denied the right to vote, and banned from jury duty, politics and the legal profession, Japanese Canadians living on the West Coast were further demeaned by a series of Orders-in-Council enacted by the government of Prime Minister Mackenzie King on February 24, 1942. Forced to relocate to primitive, crowded camps in the interior of BC, they were permitted to bring with them only what they could carry. This restriction forced Vancouver musician Harry Aoki to abandon his violin and make do with his mouth organ. Less than a year later, houses and property belonging to individuals of Japanese descent were liquidated, and auctioned off by the Custodian of Enemy Property to non-Japanese buyers for "unconscionable profits" (CDIsle).

Although Japanese Canadians were granted full citizenship status and the right to vote on March 31, 1949, formal apologies and compensation for the suffering incurred during the years of internment were slow in coming. Mackenzie King never expressed remorse about the actions of his government and even insisted that he had handled events "with loving mercy" (Marsh). It was not until September 22, 1988, that the Redress Agreement was negotiated between the National Association of Japanese Canadians and the government of Prime Minister Brian Mulroney.

The War Measures Act, a 1914 statute that enabled the federal cabinet to rule by decree when confronted with "war, invasion, or insurrection, real or apprehended" (qtd. in Smith), provided the legal basis for the actions taken against the Japanese Canadians. The broad, discretionary scope of this act allowed the internment to occur despite objections from individuals such as Major General Ken Stuart, who stated, "From the army point of view, I cannot see that the Japanese Canadians constitute the slightest menace to national security" (qtd. in Marsh). In July 1988, the War Measures Act was replaced with the Emergencies Act, a statute that is more limited in scope and that "prohibits discriminatory emergency orders" (Sunahara) such as those enacted in 1942.

Psychologists have commented on the resilience and stamina of Japanese Canadians in the context of their suffering during the internment years. This endurance is clearly evident in the musical work of Vancouver bassist and former detainee Harry Aoki. Despite, or perhaps as a result of his first-hand knowledge of the pain of extreme discrimination, Aoki has embraced and promoted the integration of musical styles from different cultures. He currently leads the First Fridays Forum at the National Nikkei Heritage Centre in Burnaby, which is described as "an outreach program with the theme of culture and identity, with the objective of sharing experience through music and dialogue" (Nikkei Place). He notes, "For communication, music is one of the easiest ways to do it," adding that, when you're dealing with art, "...you're dealing with the best part of the person" (Aoki).

Aoki chronicled the forced relocation of the Japanese Canadians in his 1998 recording project Wind Song, a collaborative work that brought together twenty musicians and several composers from all over the world. Of particular interest is the third section, which looks at how the former detainees went about rebuilding their lives in the post-war world. Here, Aoki gives a musical nod of acknowledgment to the Jewish community of Eastern Canada, which provided assistance to the Japanese Canadians who moved east of the Rocky Mountains at the end of the Second World War. This Eastward dispersal was one of two options presented to the former detainees by Prime Minister King's government; the other was deportation back to war-ravaged Japan.

Although Japanese Canadians were granted full citizenship status and the right to vote on March 31, 1949, formal apologies and compensation for the suffering incurred during the years of internment were slow in coming. Mackenzie King never expressed remorse about the actions of his government and even insisted that he had handled events "with loving mercy" (Marsh). It was not until September 22, 1988, that the Redress Agreement was negotiated between the National Association of Japanese Canadians and the government of Prime Minister Brian Mulroney.

The War Measures Act, a 1914 statute that enabled the federal cabinet to rule by decree when confronted with "war, invasion, or insurrection, real or apprehended" (qtd. in Smith), provided the legal basis for the actions taken against the Japanese Canadians. The broad, discretionary scope of this act allowed the internment to occur despite objections from individuals such as Major General Ken Stuart, who stated, "From the army point of view, I cannot see that the Japanese Canadians constitute the slightest menace to national security" (qtd. in Marsh). In July 1988, the War Measures Act was replaced with the Emergencies Act, a statute that is more limited in scope and that "prohibits discriminatory emergency orders" (Sunahara) such as those enacted in 1942.

Psychologists have commented on the resilience and stamina of Japanese Canadians in the context of their suffering during the internment years. This endurance is clearly evident in the musical work of Vancouver bassist and former detainee Harry Aoki. Despite, or perhaps as a result of his first-hand knowledge of the pain of extreme discrimination, Aoki has embraced and promoted the integration of musical styles from different cultures. He currently leads the First Fridays Forum at the National Nikkei Heritage Centre in Burnaby, which is described as "an outreach program with the theme of culture and identity, with the objective of sharing experience through music and dialogue" (Nikkei Place). He notes, "For communication, music is one of the easiest ways to do it," adding that, when you're dealing with art, "...you're dealing with the best part of the person" (Aoki).

Aoki chronicled the forced relocation of the Japanese Canadians in his 1998 recording project Wind Song, a collaborative work that brought together twenty musicians and several composers from all over the world. Of particular interest is the third section, which looks at how the former detainees went about rebuilding their lives in the post-war world. Here, Aoki gives a musical nod of acknowledgment to the Jewish community of Eastern Canada, which provided assistance to the Japanese Canadians who moved east of the Rocky Mountains at the end of the Second World War. This Eastward dispersal was one of two options presented to the former detainees by Prime Minister King's government; the other was deportation back to war-ravaged Japan.

PHOTO GALLERY

Click on thumbnail for larger image

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aoki, Harry. Personal Interview with Alan Matheson. Vancouver, BC. 2 Aug. 2006."Harry Aoki: Wind Song/Haida Dawn." CD Isle. Home Page. 12 Dec. 2007. http://www.cdisle.ca/store/

Marsh, James H. "Japanese Internment: Banished and Beyond Tears." The Canadian Encyclopedia Online. 12 Dec. 2007. http://thecanadianencyclopedia.com/

Macdonald, Bruce. Vancouver: A Visual History. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1992.

Nikkei Place. Home Page. 12 Dec. 2007. http://www.nikkeiplace.org.

Smith, Denis. "War Measures Act." The Canadian Encyclopedia Online. 12 Dec. 2007.

http://thecanadianencyclopedia.com/

Sunahara, Ann. "Japanese Canadians: Redress." The Canadian Encyclopedia Online. 12 Dec. 2007. http://thecanadianencyclopedia.com/

Vogel, Aynsley and Dana Wyse. Vancouver: A History in Photographs. Vancouver: Altitude Publishing. 1993.