EVENT

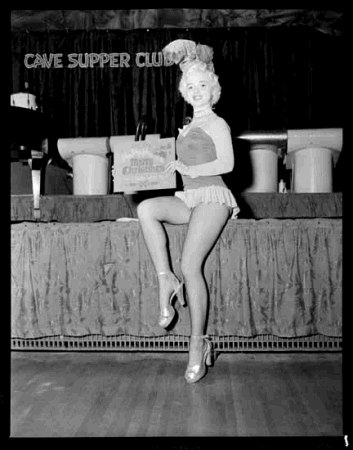

Golden Age of Striptease

1950-1975EVENT TYPE Cultural History

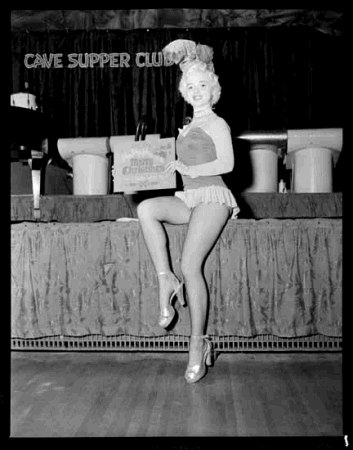

VENUES Cave, the | Isy's Supper Club | Penthouse, the

Following the end of the Second World War, newly affluent Vancouverites became free to spend their money in the pursuit of pleasure. In a period characterized by the "sexualization of popular culture," pleasure meant buying "risqué comic books, Playboy magazine, pin-up calendars, and lurid pulp novels" ("Men" 2). This trend also led to the explosion of topless dancing in local clubs across the city. In the swanky, uptown clubs of the West End, owners sought to emphasize "tasteful, Vegas-style production numbers," so as to differentiate themselves from the "raunchy" East End clubs. Floorshows at these clubs were deemed to be populated by "second-tier exotics who strutted their stuff in "Stripper-a-mas" to "B-grade" music for "the rough Chinatown crowd"" ("Men" 10). However, following British Columbia's decriminalization of nudity and bottomless dancing in 1972, club owners citywide "felt pressure to replace expensive, imported singers, comedians, and tap dancers with cheaper, exclusive line-ups of exotics" ("Men" 4).

In the upscale nightspots of the West End, such as the Cave and Isy's, exotic dancers were integrated into "cabaret-style revues" that featured a wide variety of "top-drawer" entertainment acts. Owners of these posh venues were able to draw on Vancouver's status as an established stop on the "show business railway" of the Pacific Coast in order to attract and present the latest superstars, who were accompanied in performance by Vancouver's leading jazz musicians. In this fashion, owners simultaneously employed and affirmed Vancouver's reputation for having "the hottest nightclubs North of San Francisco" ("Striptease").

There was little crossover of musicians between the West and East End clubs. Gerry Palken, who worked at Isy's as a bandleader, recalls:

"I never played the East End. We all looked down our noses at those clubs — you didn't get paid very much. It was pretty low life down there — all the down-and-outers. There was a little café that drilled holes in the spoons so the junkies wouldn't steal them to cook up. I just didn't want to work down there" (qtd. in "Men" 10).

However, black musicians like Ernie King did not have the luxury of choice regarding where they played. In reference to working at the Cave, an uptown club, Ernie comments, "I was qualified enough to play in the Cave, but they didn't want a guy like me�there were never any black musicians, unless it was a black band from the States." (qtd. in "Men" 11). Musicians and dancers of color were much more likely to get work in the East End cabarets.

The "predominance of male transients and resource workers" living in the East End/Chinatown area provided "a ready audience for relatively inexpensive floorshows" ("Men" 9). However, East End clubs were also frequented by adventurous upper class Vancouverites and tourists drawn in by Chinatown's reputation for "�catering to the consumers' taste for the extraordinary and the unusual" ("Men" 9). Club owners deliberately targeted such patrons by highlighting the multiracial nature of their floorshows, advertising "Harlem cuties, ebony sexologists, and Afro-Cuban specialists" ("Men" 10). They also made free use of the words "stripper" and "exotic," neither of which appeared in promotional material for Isy's or the Penthouse (West End clubs) until the 1970s ("Men" 10).

In the upscale nightspots of the West End, such as the Cave and Isy's, exotic dancers were integrated into "cabaret-style revues" that featured a wide variety of "top-drawer" entertainment acts. Owners of these posh venues were able to draw on Vancouver's status as an established stop on the "show business railway" of the Pacific Coast in order to attract and present the latest superstars, who were accompanied in performance by Vancouver's leading jazz musicians. In this fashion, owners simultaneously employed and affirmed Vancouver's reputation for having "the hottest nightclubs North of San Francisco" ("Striptease").

There was little crossover of musicians between the West and East End clubs. Gerry Palken, who worked at Isy's as a bandleader, recalls:

"I never played the East End. We all looked down our noses at those clubs — you didn't get paid very much. It was pretty low life down there — all the down-and-outers. There was a little café that drilled holes in the spoons so the junkies wouldn't steal them to cook up. I just didn't want to work down there" (qtd. in "Men" 10).

However, black musicians like Ernie King did not have the luxury of choice regarding where they played. In reference to working at the Cave, an uptown club, Ernie comments, "I was qualified enough to play in the Cave, but they didn't want a guy like me�there were never any black musicians, unless it was a black band from the States." (qtd. in "Men" 11). Musicians and dancers of color were much more likely to get work in the East End cabarets.

The "predominance of male transients and resource workers" living in the East End/Chinatown area provided "a ready audience for relatively inexpensive floorshows" ("Men" 9). However, East End clubs were also frequented by adventurous upper class Vancouverites and tourists drawn in by Chinatown's reputation for "�catering to the consumers' taste for the extraordinary and the unusual" ("Men" 9). Club owners deliberately targeted such patrons by highlighting the multiracial nature of their floorshows, advertising "Harlem cuties, ebony sexologists, and Afro-Cuban specialists" ("Men" 10). They also made free use of the words "stripper" and "exotic," neither of which appeared in promotional material for Isy's or the Penthouse (West End clubs) until the 1970s ("Men" 10).

PHOTO GALLERY

Click on thumbnail for larger image

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ross, Becki. "Men Behind the Marquee: Greasing the Wheels of Vansterdam's Professional Striptease Scene, 1950-1975." The Striptease Project. 2008.Ross, Becki. "The Striptease Project: Details." Research in Arts. Home page. University of British Columbia Faculty of Arts. 29 Feb. 2008. http://www.arts.ubc.ca/index.php?id=467&backPID=479&tt_news=21