EVENT

As black settlers migrated west from the prairies in search of improved economic prospects, a small black community became established in Strathcona, in Vancouver's culturally diverse East End. The development of this neighborhood was due in part to its proximity to the terminal for the CN Railroad, which was the chief employer for black men at the time. However, the heart of the community was unquestionably a lane casually referred to as Hogan's Alley. This street provided access to the African Methodist Episcopal Fountain Chapel, which was an important social and religious centre for the community, as well as to various nightclubs, gambling houses, and restaurants. These lively establishments earned the area the nickname of "Vancouver's square mile of sin" (Walling), and were subject to intense scrutiny by the Vancouver Police. As dancer, choreographer, and community resident Len Gibson recalls, the "amoral" quarter was eventually declared "an urban blight" (qtd in"Blues"), which continued to decline into disrepair as the black population dispersed throughout Greater Vancouver. In 1972, the construction of an off ramp for the Georgia Viaduct, part of the Urban Renewal Project, "effectively obliterated" (Compton) what was left of the community.

Performer and former Strathcona resident Thelma Gibson-Towns has described the population of this working class neighborhood as "one big family" (Hogan's). She remembers the sense of togetherness and social communion generated by singing gospel music in the church, and notes that she knew all of the patrons who came into the restaurant where she waited tables.

Serving in a "chicken shack," as the black-run restaurants of the neighborhood were known, was one of the few occupations open to the local black women. These popular "joints" were open from 5pm to 5am, and offered a fare of Southern-style fried chicken, potato salad, corn fritters, and navy beans. According to Gibson-Towns, the "chicken shacks" were popular amongst both the longshoremen, who would come in for a hearty evening meal around 6 o'clock, and the late night crowd. After the beer parlors of the area closed, the restaurants essentially became bottle clubs, with patrons socializing and dancing to the jukebox.

The only official, all-black nightclub in Vancouver was the Harlem Nocturne, which was owned and operated by trombonist Ernie King and his wife Marcella "Choo Choo" Williams. As an East End club, the Harlem Nocturne drew the attention of both the police and of "thrill-seeking white Vancouverites and tourists," who were attracted by the area's reputation for "adventure, intrigue, vice, and immorality" (Ross 9). Unable to secure liquor licenses until 1969, venues in the East End operated as illegal bottle clubs, making police raids commonplace. King, however, felt singled out by the vice squad: "No one was harassed more than me. No one. It got to the point they would harass me two or three times a night. Because I was the only man that owned a black nightclub!" (Ross 11).

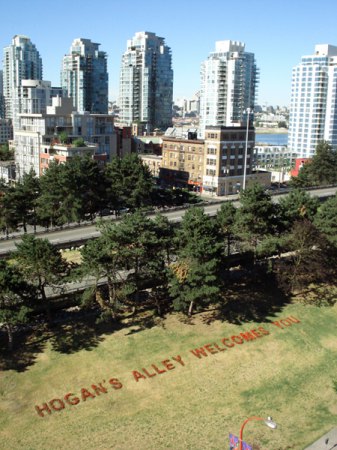

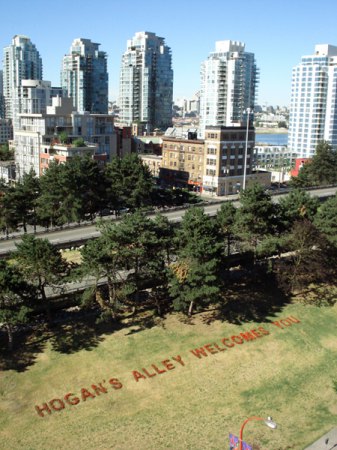

Today, what little remains of Hogan's Alley has been assimilated into Chinatown, and "bears no mark that there was ever a black presence there" (Compton). However, the legacy of the community continues to live on through the work of groups such as the Hogan's Alley Memorial Project, which is dedicated to "memorializing Vancouver's historic black neighborhood and the wider Vancouver black experience." Its members work to remind the public of 'the need to remember forgotten minorities" ("HAMP").

Performer and former Strathcona resident Thelma Gibson-Towns has described the population of this working class neighborhood as "one big family" (Hogan's). She remembers the sense of togetherness and social communion generated by singing gospel music in the church, and notes that she knew all of the patrons who came into the restaurant where she waited tables.

Serving in a "chicken shack," as the black-run restaurants of the neighborhood were known, was one of the few occupations open to the local black women. These popular "joints" were open from 5pm to 5am, and offered a fare of Southern-style fried chicken, potato salad, corn fritters, and navy beans. According to Gibson-Towns, the "chicken shacks" were popular amongst both the longshoremen, who would come in for a hearty evening meal around 6 o'clock, and the late night crowd. After the beer parlors of the area closed, the restaurants essentially became bottle clubs, with patrons socializing and dancing to the jukebox.

The only official, all-black nightclub in Vancouver was the Harlem Nocturne, which was owned and operated by trombonist Ernie King and his wife Marcella "Choo Choo" Williams. As an East End club, the Harlem Nocturne drew the attention of both the police and of "thrill-seeking white Vancouverites and tourists," who were attracted by the area's reputation for "adventure, intrigue, vice, and immorality" (Ross 9). Unable to secure liquor licenses until 1969, venues in the East End operated as illegal bottle clubs, making police raids commonplace. King, however, felt singled out by the vice squad: "No one was harassed more than me. No one. It got to the point they would harass me two or three times a night. Because I was the only man that owned a black nightclub!" (Ross 11).

Today, what little remains of Hogan's Alley has been assimilated into Chinatown, and "bears no mark that there was ever a black presence there" (Compton). However, the legacy of the community continues to live on through the work of groups such as the Hogan's Alley Memorial Project, which is dedicated to "memorializing Vancouver's historic black neighborhood and the wider Vancouver black experience." Its members work to remind the public of 'the need to remember forgotten minorities" ("HAMP").

PHOTO GALLERY

Click on thumbnail for larger image

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Compton, Wayde. "Hogan's Alley Memorial Project." Personal Home page. 3 Jan 2008.http://www.sfu.ca/~wcompton/index10.html.

"HAMP at Under the Volcano Festival, August 12, 2007." Online Posting. 14 Aug 2007. Hogan's Alley Memorial Project. 3 Jan 2008. http://www.hogansalleyproject.blogspot.com.

Hogan's Alley. Dir. Andrea Fatona and Cornelia Wyngaarden. Video. 1994

Montague, Tony. "Blues Salutes Historic Black Community." Georgia Straight, 19 Oct 2006. Online Archive. 3 Jan 2008. http://www.straight.com/blues-salutes-historic-black-community.

Ross, Becki. "Men Behind the Marquee: Greasing the Wheels of Vansterdam's Professional Striptease Scene, 1950-1975." The Striptease Project. 2008.

Walling, Savannah. "Memories of the Downtown Eastside's Black Community." Carnegie Newletter 15 Sept. 2006. Online version. 11 May 2008. http://carnegie.vcn.bc.ca/index.pl/september_1506_page01